WARNING: May contain PG-13 material. Do not read if underage...

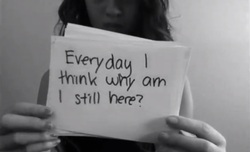

Last year a fifteen year-old, Amanda Todd, sadly decided to end her life due to being a victim of severe bullying. In a Youtube video left behind, she told the story by flash card set to a maudlin song 'Hear To Me' her story is this. A few years ago, she was chatting with someone she met online, a man who flattered her. At his request, she flashed him. The man took a picture of her breasts. He then proceeded to follow Todd around the Internet for years. He asked her to put on another show for him, but she refused. So he’d find her classmates on Facebook and send them the photograph. To cope with the anxiety, Todd descended into drugs and alcohol and ill-advised flirtations and sex. Her classmates ostracized her. She attempted suicide a few times before finally succeeding. Todd’s suicide is easily analogized to Tyler Clementi’s, mostly because the public has diagnosed both cases as the result of “cyber-bullying.” Yet, as a descriptive term, “cyber-bullying” feels deliberately vague. Somewhere in the midst of the “mob” there is usually at least one person whose cruelty exceeds the tossing off of a stray insult. In Clementi’s case, the magazine’s Ian Parker chalked the harasser’s motives up to “shiftiness and bad faith,” the kinds of things that criminal statutes can’t easily be invoked to cover. But with Todd’s harasser, the malice is unquestionable. Anyone who has ever been to high school knows what they are provoking by distributing photographs like that.

Last year a fifteen year-old, Amanda Todd, sadly decided to end her life due to being a victim of severe bullying. In a Youtube video left behind, she told the story by flash card set to a maudlin song 'Hear To Me' her story is this. A few years ago, she was chatting with someone she met online, a man who flattered her. At his request, she flashed him. The man took a picture of her breasts. He then proceeded to follow Todd around the Internet for years. He asked her to put on another show for him, but she refused. So he’d find her classmates on Facebook and send them the photograph. To cope with the anxiety, Todd descended into drugs and alcohol and ill-advised flirtations and sex. Her classmates ostracized her. She attempted suicide a few times before finally succeeding. Todd’s suicide is easily analogized to Tyler Clementi’s, mostly because the public has diagnosed both cases as the result of “cyber-bullying.” Yet, as a descriptive term, “cyber-bullying” feels deliberately vague. Somewhere in the midst of the “mob” there is usually at least one person whose cruelty exceeds the tossing off of a stray insult. In Clementi’s case, the magazine’s Ian Parker chalked the harasser’s motives up to “shiftiness and bad faith,” the kinds of things that criminal statutes can’t easily be invoked to cover. But with Todd’s harasser, the malice is unquestionable. Anyone who has ever been to high school knows what they are provoking by distributing photographs like that.

It is a cultural myth—one particular to the Internet—that the methods of a harasser are fundamentally “legal,” and that the state is helpless to intervene in all cases like this. The systematic way the harasser allegedly followed Todd to new schools, repeatedly posting the images and threatening to do it again, makes it textbook harassment regardless of the medium. Indeed, in Todd’s native Canada, cyber-harassment is prosecuted under the general harassment provision of the Canadian criminal code. And in the United States, most states have added specific laws against cyber-harassment and bullying to their general legislation of harassment. At the federal level, there is the Federal Interstate Stalking Punishment and Prevention Act, which covers harassment that crosses state and national lines. While all of these laws are subject to the limitations of the First Amendment, the First Amendment generally doesn’t protect threats and harassment. If people are not being prosecuted for these acts, the fault lies in the social alchemy of law enforcement, the way the human prejudices of judges, juries, and prosecutors inflect the black letter. Put otherwise, the power is there—the cultural mores are what is preventing the laws from being successfully invoked.

There are, after all, consequences to the widespread belief that these acts of harassment are regrettable but not ultimately punishable. Specifically, it obscures truths about the practice—first, that this kind of thing is not merely the province of children who know not what they do. While the police have yet to confirm the identity of Todd’s harasser, the “hacktivist” group Anonymous has identified an adult man who lived nearby as the culprit. (He denies the harassment, though he told a Canadian television news crew that he did indeed know Todd.) It remains to be seen whether they’ve pointed the finger at the right person. But the theory—that an adult would have targeted a teen-ager for such abuse, that he would have tricked her and been indifferent to the price she paid—is not merely plausible. It is a thing that happens every day on the Internet. To wit: only two days after Todd’s suicide, the Gawker reporter Adrian Chen identified a man named Michael Brutsch as one of the moderators of certain venal sub-threads on the “social news” Web site Reddit. Some were dedicated to “creepshots” and “jailbait.” They functioned chiefly as vehicles for the delivery of pictures of young women, many of whom did not consent to either the taking of the photograph or this particular mode of dissemination. The jail-bait photographs, typically of teen-age girls in the theatrical (if minimally clothed) poses that used to be the exclusive province of bedroom mirrors, tended to be stolen from teen-agers’ Facebook pages. The “creepshots,” by contrast, were usually taken furtively, without the notice of the subject who, leaning over a table, or sitting in a chair, did not imagine herself to be giving a show.

Brutsch and co., who are merely a small subgroup of a large and vocal population, argue that they do nothing wrong in posting—or facilitating the posting of—these images. They are, they say, merely engaging in the vaunted American tradition of “free speech,” which is what makes their activities “legal.” Any consequences are therefore “illegal.” Any civil or criminal liability of his own—under, say, Texas Penal Code provisions that prevent the non-consensual taking and transmission of photographs “to arouse or gratify the sexual desire of any person,” or even a suit for copyright infringement from a young woman whose image he has re-posted—has not even crossed Brutsch’s mind. The only kind of lawyer he has hinted at hiring is a plaintiff’s attorney who would work on a contingency fee and help him sue Gawker. On what grounds, he didn’t say, but one guesses that he’s thinking about the so-called reputational torts—suits for defamation, or invasion of privacy. Irony has no dominion here. What you could call the Brutschean world view—which takes anonymity as the only meaningful form of privacy, and a key element of free speech—is nearly an article of faith in these lower levels of the Internet. But it has tentacles that extend to higher, more powerful places. Scholars often approvingly quote EFF.org founder John Perry Barlow’s “Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace,” which, among other utopian visions, holds that “our identities have no bodies, so, unlike you, we cannot obtain order by physical coercion.” The founding myth of the Internet was its offer of a way to escape physical reality; the freedom to shape yourself, to say anything, became a sort of sacred object.

But, as the scholar Mary Anne Franks has observed, women haven’t actually achieved this “bodiless” freedom online. They are embodied in distributed pictures and in sexual comments, whether they like it or not. The power to get away from yourself, like everything else, is unevenly distributed. Women have become, as Franks put it, “unwilling avatars,” unable to control their own images online, and then told to put up with it for the sake of “freedom,” for the good of the community. And then they are incorrectly told, even if the public is behind them, that they have no remedies in the law. They are shouted down by people with a view of freedom of speech more literal than that held by any judge. You can, of course, take these points too far. It is dreadfully easy, nowadays, to turn tragedy into a one-note martyrdom. In “The Savage God,” the critic A. Alvarez observes, “A suicide’s excuses are mostly casual.” Her real motives “belong to the internal world, devious, contradictory, labyrinthine, and mostly out of sight.” But whatever Amanda Todd might have been thinking, whatever else might be true, she did get one thing out of this: Amanda Todd did manage to, just once, tell her own story. She got to drown out the version of her that strangers had put out on the Web. It’s a small comfort. But it was perhaps the only one she had left...

There are, after all, consequences to the widespread belief that these acts of harassment are regrettable but not ultimately punishable. Specifically, it obscures truths about the practice—first, that this kind of thing is not merely the province of children who know not what they do. While the police have yet to confirm the identity of Todd’s harasser, the “hacktivist” group Anonymous has identified an adult man who lived nearby as the culprit. (He denies the harassment, though he told a Canadian television news crew that he did indeed know Todd.) It remains to be seen whether they’ve pointed the finger at the right person. But the theory—that an adult would have targeted a teen-ager for such abuse, that he would have tricked her and been indifferent to the price she paid—is not merely plausible. It is a thing that happens every day on the Internet. To wit: only two days after Todd’s suicide, the Gawker reporter Adrian Chen identified a man named Michael Brutsch as one of the moderators of certain venal sub-threads on the “social news” Web site Reddit. Some were dedicated to “creepshots” and “jailbait.” They functioned chiefly as vehicles for the delivery of pictures of young women, many of whom did not consent to either the taking of the photograph or this particular mode of dissemination. The jail-bait photographs, typically of teen-age girls in the theatrical (if minimally clothed) poses that used to be the exclusive province of bedroom mirrors, tended to be stolen from teen-agers’ Facebook pages. The “creepshots,” by contrast, were usually taken furtively, without the notice of the subject who, leaning over a table, or sitting in a chair, did not imagine herself to be giving a show.

Brutsch and co., who are merely a small subgroup of a large and vocal population, argue that they do nothing wrong in posting—or facilitating the posting of—these images. They are, they say, merely engaging in the vaunted American tradition of “free speech,” which is what makes their activities “legal.” Any consequences are therefore “illegal.” Any civil or criminal liability of his own—under, say, Texas Penal Code provisions that prevent the non-consensual taking and transmission of photographs “to arouse or gratify the sexual desire of any person,” or even a suit for copyright infringement from a young woman whose image he has re-posted—has not even crossed Brutsch’s mind. The only kind of lawyer he has hinted at hiring is a plaintiff’s attorney who would work on a contingency fee and help him sue Gawker. On what grounds, he didn’t say, but one guesses that he’s thinking about the so-called reputational torts—suits for defamation, or invasion of privacy. Irony has no dominion here. What you could call the Brutschean world view—which takes anonymity as the only meaningful form of privacy, and a key element of free speech—is nearly an article of faith in these lower levels of the Internet. But it has tentacles that extend to higher, more powerful places. Scholars often approvingly quote EFF.org founder John Perry Barlow’s “Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace,” which, among other utopian visions, holds that “our identities have no bodies, so, unlike you, we cannot obtain order by physical coercion.” The founding myth of the Internet was its offer of a way to escape physical reality; the freedom to shape yourself, to say anything, became a sort of sacred object.

But, as the scholar Mary Anne Franks has observed, women haven’t actually achieved this “bodiless” freedom online. They are embodied in distributed pictures and in sexual comments, whether they like it or not. The power to get away from yourself, like everything else, is unevenly distributed. Women have become, as Franks put it, “unwilling avatars,” unable to control their own images online, and then told to put up with it for the sake of “freedom,” for the good of the community. And then they are incorrectly told, even if the public is behind them, that they have no remedies in the law. They are shouted down by people with a view of freedom of speech more literal than that held by any judge. You can, of course, take these points too far. It is dreadfully easy, nowadays, to turn tragedy into a one-note martyrdom. In “The Savage God,” the critic A. Alvarez observes, “A suicide’s excuses are mostly casual.” Her real motives “belong to the internal world, devious, contradictory, labyrinthine, and mostly out of sight.” But whatever Amanda Todd might have been thinking, whatever else might be true, she did get one thing out of this: Amanda Todd did manage to, just once, tell her own story. She got to drown out the version of her that strangers had put out on the Web. It’s a small comfort. But it was perhaps the only one she had left...

RSS Feed

RSS Feed